A groundbreaking carbon-capture machine, known as Mammoth, has garnered international attention since it was activated in May on Iceland’s geothermal plains. This enormous vacuum cleaner, designed to extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, can remove up to 36,000 tonnes of CO₂ annually and lock it underground in a fossilized form.

Mammoth, developed by the Swiss company Climeworks, is ten times the size of their previous machine. However, it will soon be outdone by larger carbon-capture devices being built in the United States, Norway, Kenya, and Oman. Climeworks plans to dramatically expand its operations, leveraging abundant wind and solar power to operate machines capable of capturing millions of tonnes of CO₂ per year by 2030, with a target of one billion tonnes annually by 2050.

Oscar Schily, Climeworks’ head of climate policy, is currently in Australia for a conference and discussions with government officials about potential expansion. While he acknowledges that carbon removal technology alone won’t solve climate change, Schily emphasizes its necessity alongside aggressive emission reductions. UN climate models indicate that even with ambitious emission cuts, between seven and 14 billion tonnes of CO₂ must be removed from the atmosphere annually by mid-century to maintain safe climate conditions.

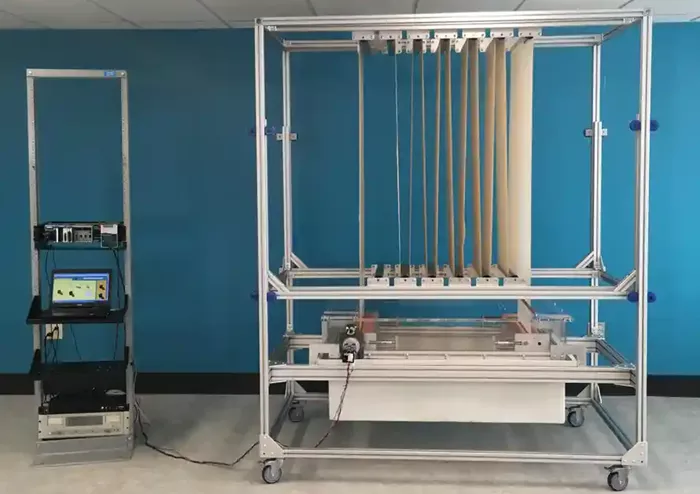

Forests will play a significant role in this carbon removal, but technological solutions like those offered by Climeworks are also crucial. Schily highlights the aesthetic and tangible appeal of their machines, exemplified by Mammoth’s impressive air intake fans and clean energy operation in Iceland. The device works by drawing air through containers, passing it over solid filters to extract carbon, which is then injected into basalt rock to mineralize into stone.

Australia, with its vast open spaces and planned renewable and hydrogen infrastructure in states like NSW, SA, and WA, is a prime candidate for hosting such a machine. However, carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies have faced criticism from climate scientists and activists, who argue it can be an expensive, risky diversion or a form of corporate greenwashing. The Gorgon gas project in Australia, which was supposed to capture 80% of its emissions, has struggled to meet its targets, reinforcing skepticism about CCS’s effectiveness.

Greg Bourne, a former BP executive now with the Climate Council, points out that the fossil fuel industry often uses captured CO₂ to extract more oil, furthering emissions. He warns that technological solutions can divert attention and resources from proven clean energy investments. Despite this, Bourne concedes that direct air capture, like that developed by Climeworks, could become vital in addressing climate change.

Schily insists that Climeworks aims to address historical emissions without extending the fossil fuel industry’s lifespan. Their focus on direct air capture from the atmosphere, rather than industrial emissions, underscores their commitment to aiding decarbonization and achieving net-zero emissions.

“We are not here to give license to industry to keep polluting,” Schily asserts. “We are here to help solve the problem of historical emissions and to help reach net zero.”